By Wendell Steavenson

Abu Anas, an intelligent man in his 40s going grey at the temples, was delighted when, in July, he received a permit to work in Israel. In Gaza he made no more than $10 a day as a labourer, when he could find the work; in Israel he could earn ten times as much on construction sites. Like many Gazans who found regular jobs in Israel, he lodged in Rahat, a Bedouin Arab city in the south of the country for several weeks at a time. “When the war began, we were worried. We didn’t feel safe,” Abu Anas, who didn’t want me to use his real name, told me.

For a few days, he continued to go to work until he lost hope that the “situation would calm down”. On October 11th the Israeli government revoked all permits to enter Israel issued to Gaza residents. It was now illegal for the 10,000 or so Gazans who found themselves in Israel to remain there. But the crossing into Gaza had been closed, so Abu Anas was stranded.

Then his landlord asked him to leave. Under Israeli law, people can be fined or imprisoned for harbouring illegal Palestinians. Abu Anas’s landlord advised him to present himself voluntarily at the police station and ask to be taken to the West Bank. When Abu Anas and a group of Gazans went to the Israeli police, about a week after the war began, they were arrested. Abu Anas said their phones, belongings and clothes were taken away, they were searched and beaten, and put in a crowded cell, with no furniture or bedding, with around 40 other Gazans. (A spokesman for the Israeli police said they couldn’t comment on individual cases but said that any Gazans in the country illegally would be “lawfully arrested”.)

The following day, he and some other Gazans were blindfolded, handcuffed, put on buses and taken to Ofer, an Israeli military camp and prison in the West Bank, near Ramallah. According to Abu Anas, when they arrived they were pushed to the ground, beaten again and placed in a large tent with over 200 other workers from Gaza. “I met several people from the same neighbourhood as me,” he said. They were not permitted, he said, to leave their tent, but some learnt that there were several similar ones, also full of Gazan workers. No explanation was given for their detention and they had no access to lawyers or the Red Cross.

The men slept on the ground on crude wooden pallets. Rain leaked through the roof of the tent. The only clothes Abu Anas had with him were the ones he was arrested in. “I washed them and put them back on wet, to dry.”

Abu Anas told me he spent 15 days in detention at Ofer. He was then put on a bus with some other men – he couldn’t tell how many exactly because he’d been blindfolded. He and about ten others were told to get out at a checkpoint on the road to Ramallah in territory administered by the Palestinian Authority. His ID documents were returned to him, though his mobile phone, his money and other belongings were not. He was abandoned in unfamiliar surroundings, penniless and desperately worried about his family in Gaza.

After October 7th, Jessica Montell, the head of HaMoked, an Israeli human-rights organisation that helps Palestinian prisoners, received hundreds of calls a day. Some were from Gazan workers who were frightened and in hiding in Israel; others were from their family members in Gaza who had lost contact with them.

“The calls from Gaza were chilling,” she told me.“You hear the bombardment in the background. Sometimes the call was suddenly cut off. One of my colleagues told me she had a call from a woman who was frantic to find her brother. She said ‘I have to tell him his son was killed.’”

HaMoked gathered names and ID numbers of missing Gazan workers and filed a habeas corpus petition to find out where they were. Press reports, citing Israel Defence Force (IDF) officials, suggested that 4,000 workers from Gaza were being held in military detention.

Over the next couple of weeks, from talking to three Gazan workers who had been released, HaMoked learnt that the workers were being held at three locations – all of them military camps. One of the Gazans HaMoked talked to said he had been held in a cage “like a chicken coop”, open to the elements and with no food, water, medication, bedding or toilets. A spokesman for the IDF said that “no complaints were received regarding abuse and violence…Detainees were provided shelter, as well as food and water throughout the day. Additionally, each facility had a medical team.”

The attacks of October 7th also prompted a crackdown across the West Bank. Hundreds of Palestinians living there have been arrested, family visits stopped and lawyers report that they have very limited access to their clients.

Meanwhile thousands of Gazan workers began arriving in the West Bank – some dumped at checkpoints by Israeli police or soldiers; some having made their own way, after paying two or three times the usual rate to drivers who knew back routes to avoid checkpoints. Hamdan al-Barghouti, deputy governor of Ramallah and Al-Bireh, told me that by the beginning of November there were 6,000 Gazan workers in the West Bank, as well as about 100 Gazans who had been receiving treatment in hospitals in Israel and East Jerusalem. They had been told to leave along with the relatives who accompanied them. He said that the Palestinian Authority had had no communication with Israeli authorities on the subject of stranded Gazans. “It was not organised,” he told me.

I met Abu Anas at a sports complex in Ramallah (pictured) where the Palestinian Authority was housing about 500 Gazan workers. The men – many of whom were dressed in grimy and torn jeans or joggers, T-shirts and sweatshirts – milled around the large courtyard. They passed callused hands over their faces, chewing fingernails with their heads bent over the cracked screens of their mobile phones, as they scrolled through the terrible news from Gaza. Volunteers handed out meals of yellow rice and vegetables in polystyrene clamshells. Some washed themselves in a row of portable toilets with handheld showers.

One man, a trained civil engineer who worked in a shawarma restaurant in Haifa, sat on a foam mattress, looking sadly into his phone. “There’s no good internet here,” he told me. “Yesterday I called my young daughter, and I told her that after this war I will take her and her mother to a nice restaurant and to the zoo. She told me, ‘Dad, I don’t need so much. I just want to hug you and feel safe and peace again.’”

Another man nearby held up his phone so I could listen to the automated message informing him to evacuate from north Gaza to the south for his own safety. “I got this call three days ago, even though I am here in Ramallah,” he said. “More than 80% of the men”, one of the volunteers told me, “have relatives who have been killed. An hour and a half ago one learned that his whole family – six sons and his wife – had been killed. He fainted and we called an ambulance.”

Abu Anas has four children: the youngest is a year old, the eldest is 12. They live in Khan Younis in the south of Gaza. “Our apartment is still standing,” he told me, “but everywhere is bombed and everyone is afraid.” He said his wife and children were moving around, sleeping in different places in order to keep safe. “It is miserable there.” He has to borrow a mobile phone to reach his family. “Sometimes I am embarrassed to ask people,” he told me.

Inside the vaulted sports hall was a jumbled sea of foam mattresses heaped with blankets. Shopping bags of possessions were stowed next to plastic sandals and toilet rolls. Snaking wires connected phones to electricity sockets. Abu Anas surveyed the shipwreck. “All we talk about is how many massacres there were today, how many children killed, how many deaths. Of course we are angry. But we are not responsible for what happened. We didn’t do anything. We were working with their permission. We are peaceful. I don’t support violence from any party. Now we are prisoners here. We don’t know what the future holds…No one feels safe because at any moment the Israelis can enter and arrest us.”

I talked to dozens of Gazan workers who recounted different versions of the same story: fear of leaving their lodgings, price-gouging by drivers, difficulties in contacting their families in Gaza, loved ones killed or injured, relatives and friends who worked in Israel now missing, presumed detained.

A month into the war, Gazan workers stranded in Israel were still arriving in the West Bank. One newcomer told me he had been hiding for four weeks in Nazareth, a largely Arab city in the north of Israel, waiting for an opportunity to cross to the West Bank without being seized by the police. I spoke to three men who told me that they had remained in their flat in Ramle, near Tel Aviv, for more than two weeks, while friends brought them food. Even then, they were arrested by police who raided their apartment one morning in the early hours. They said they had been beaten, hooded, abused with insults in Arabic, imprisoned in Ramle for four days and dumped at the Ramallah checkpoint. I saw blisters and scabs, the hallmarks of cable ties, around the wrists of several men. Some had been hospitalised in Ramallah as a result of their beatings.

The night I met Abu Anas, the Israeli government issued a press release. It said: “Israel is severing all contact with Gaza,” and that all Gazan workers in the country would be returned home.

The following morning news outlets carried footage of around a hundred people returning to Gaza through the Kerem Shalom crossing at the south of the territory. Their hands were empty. Some didn’t even have shoes. A day later I went back to see the Gazan workers in the sports complex. Several had heard through the grapevine of friends and relatives who had been transferred to Gaza.

A man called Abu Adam told me his brother was one of those released. “I called my brother’s wife and she passed me the phone and I was able to talk to my brother in Khan Younis [a refugee camp in Gaza].” Abu Adam said we were “happy” to see them leave. “We all want to return. I would prefer to be in Gaza, not here. There is my family, my children, my wife. If they should die and I remain alive here? It would be a life without meaning.” ■

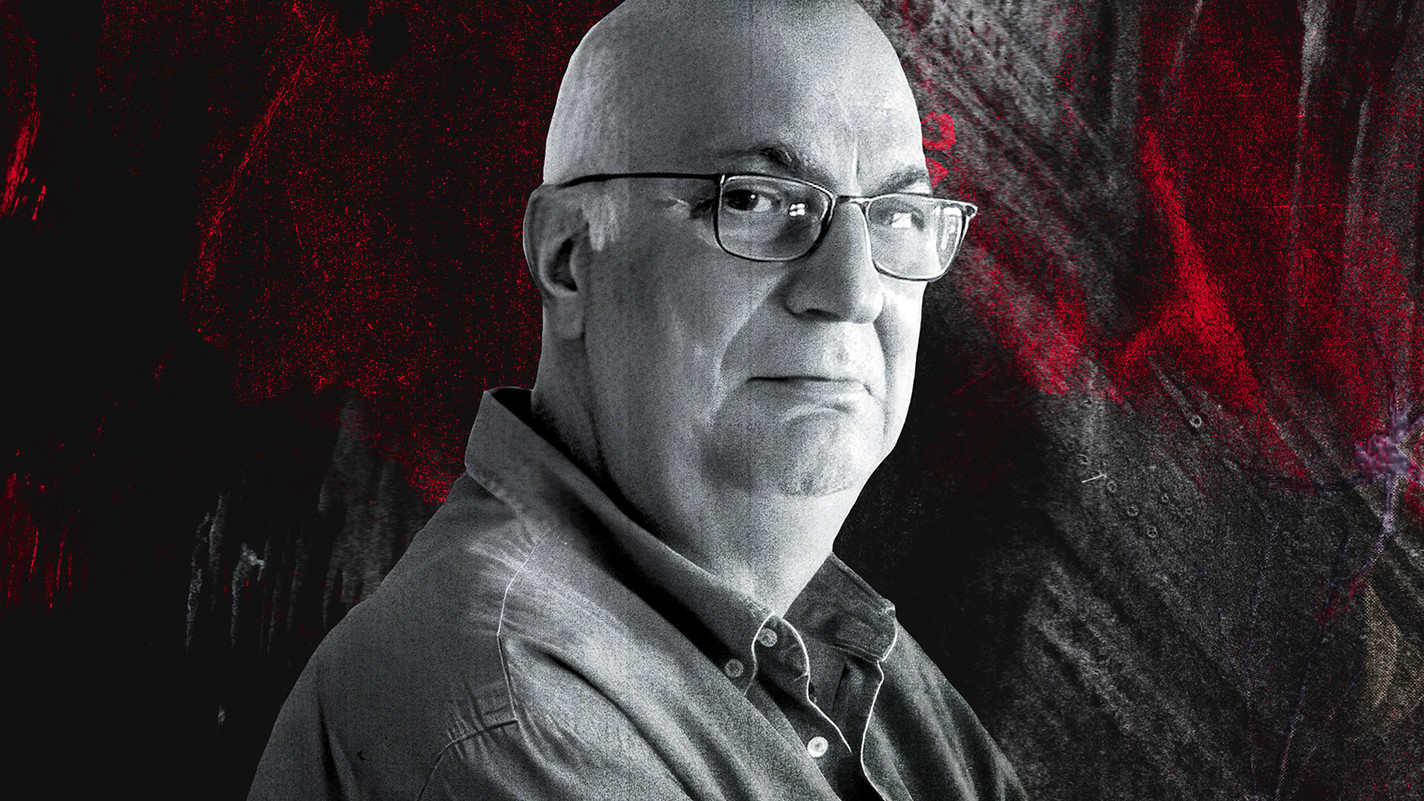

Wendell Steavenson has reported on the Iraq war, the Egyptian revolution and war in Ukraine. You can read her previous dispatches from Israel for 1843 magazine, and the rest of our coverage, here.

PHOTOGRAPHS TANYA HABJOUQA

More from 1843 magazine

Anyone can break a Guinness World Record. I did

Consultants are designing bespoke awards to help companies build their brands

The biblical archaeologist finding the victims Hamas burned

Bodies have been reduced to ash. Entire families are wiped out. Dismembered limbs are jumbled together

Israel’s top hostage negotiator on dealing with Hamas

In 2011 David Meidan managed to get one person out of Gaza. Now he’s trying to free 240