By Barclay Bram

On an overcast spring day in Southampton, a city on the south coast of England, a man wearing a jetpack was about to go head to head with a hurdler. Nearby, the inventors of the world’s fastest wheelbarrow, toilet and wheelie bin were getting ready to race their motorised contraptions against each other (the fastest, it turns out, was the toilet). At the other end of the running track stood a bearded adjudicator, wearing a dark-blue suit with silver piping and a badge that read “Guinness World Records”.

What do you think of when you imagine a world record? Maybe Usain Bolt and the 9.58 seconds it took him to run 100 metres, or Elizabeth II, the longest-reigning queen of England, or the Mariana Trench, the deepest point in the ocean. You could be forgiven for not considering the fastest time for a person wearing a jetpack to complete a hurdles course – 42.06 seconds, incidentally – to be a legitimate sort of record.

But the people behind the Guinness World Records (GWR), who have been judging the world’s fastest, strongest and tallest since the 1950s, are more open-minded. This attitude is partly born out of sincerity – GWR employees tend to be comically passionate and nerdy about record-breaking. But, increasingly, it is also about money. The record-breaking event in Southampton had been sponsored by an electronics company that was trying to market a phone charger.

When I was growing up, in the 1990s, the “Guinness Book of Records” was the bestselling copyrighted book in the world. But the dawn of the digital age – and the declining interest in print books – forced GWR to pivot. Today the bulk of the company’s revenue comes from brand partnerships and the production of digital content. For a fee that starts at £11,000, a company or individual can hire GWR to help them set or break a record. GWR’s “consultants” will advise on the logistics involved in staging and adjudicating the attempt, while its in-house production team will film content and edit it into social-media-friendly clips.

In today’s attention economy, where brands and influencers are desperately vying to be noticed among endless streams of content, the GWR’s ability to bestow the title of “world’s greatest” is valuable intellectual property. Virgin Media set a record for the fastest team downhill skateboard – an advert for broadband – and Honda built the largest rugby-ball mosaic as a team-bonding exercise. (A telling quote from GWR’s website: “Not only did we set a Guinness World Records title for the largest item unboxed, we set the record for the most-watched film from Volvo Trucks North America.”)

Keen to find out more about what GWR calls a “bespoke record-based solution”, I spoke to Lewis Blakeman, GWR’s head of record content support who had offered to help me find the one thing that I could be singularly great at. Blakeman started by asking me questions about my interests; in many ways, this stage of the process had all the tentative awkwardness of a first date. I told him I work in the audio department at The Economist. Maybe, I suggested, I could try a record based on listening to a lot of podcasts?

“The issue there would be defining listening,” Blakeman told me. “It’s the same for reading. We don’t have any records for reading in and of itself because how can you prove that someone has actually read the thing they say they have?” Records have to be verifiable by a third party and standardisable, so another person can attempt the exact same record. They also have to have a single, clearly measurable variable. (GWR does have a record for the longest time spent reading out loud, as that can be measured.)

If I couldn’t find a record directly related to my career, maybe there would be one I could tie into my passions. Before The Economist I worked as a chef. Blakeman noted that Gordon Ramsay held the record for filleting a fish in the fastest amount of time. The thought of taking Ramsay down a peg appealed, but I’m an aspiring vegan. “Well, there’s a record for the most slices of a cucumber,” said Blakeman. It has stood since 1983 and involves slicing a 30.5cm cucumber, 3.8cm in diameter, into at least 264 slices – each slice 1.1mm thick – in 13.4 seconds. I lifted my hands off the keyboard and admired the fact I still retained eight fingers and two thumbs. Blakeman said he would come back to me with some ideas related to two of my other hobbies, yoga and cycling.

As we hung up I was struck by the fact that much of his job involved working out how to define and measure things. Earlier employees of GWR had different aims. Indeed, the Guinness World Records were created by Arthur Guinness and Sons as a canny way to market the brewery’s stout. The managing director, Sir Hugh Beaver, hired Ross and Norris McWhirter – Oxford-educated twins who ran a fact-finding agency for newspapers and other publications – to compile a book of facts that would provide definitive answers to questions people might argue about in pubs. The first edition of “The Guinness Book of World Records”, published in 1955, reflected the world as its creators found it, with its discrete facts checked by the book’s editorial staff.

Although the book became extremely popular, Norris began to sour on the direction GWR was taking (Ross was killed by the IRA in 1975). The book became less a record of the world as it was, and more a reflection of the lengths certain people will go to be considered the best at something. People had started to create and beat records to get into the book itself, and it started to feature more records involving rich and famous people – like Richard Branson, who set numerous records for hot-air ballooning and other stunts. In 1999 Norris – now no longer working at the company – published his own, more sober alternative, called the “Book of Millennium Records” (it was a flop). In 2004 he died playing tennis; just a few months later “Guinness World Records 2004” would sell its 100 millionth copy.

But a shift was already under way which would have no doubt caused McWhirter even more disappointment. In 2001 Guinness’s parent company had decided to sell off GWR. After changing hands a few times, GWR was acquired, in 2008, by the Jim Pattison group, the owners of the Ripley’s Believe it Or Not franchise, which is known for promoting strange or bizarre events and objects. There were obvious similarities between Ripley’s museums of oddities and a book which for decades had celebrated people like Shridhar Chillal, the man with the longest fingernails. (After 66 years, Chillal cut them off. The nails – the longest of which is 197.8 cm – now hang in the Ripley’s museums in New York and Amsterdam.) In 2009 GWR’s “consultancy” was born.

Larry Olmsted, who wrote a memoir about getting into the “Guinness Book of Records”, told me that he sees record-breaking and GWR’s early history “as a precursor to reality TV”. Olmsted broke the record for farthest distance between two rounds of golf played in a single day (at courses in Sydney and Los Angeles); he also set the record for longest continuous poker match (72 hours straight). “The Guinness World Records were sort of the original way of saying, ‘Hey, look at me, I’m important. I’m special’,” he said.

There was also something democratic, he felt, about the Guinness World Records that helped cement its mass appeal. “When I broke the golf record the rules clearly stipulated I had to fly by commercial jet liner,” Olmsted said. “This way you wouldn’t have someone like Bill Gates fly in his Gulfstream and take the record.”

When I told him that a consultant was helping me find a record to beat, Olmsted raised an eyebrow. From 1997 the number of records exceeded the capacity of the book, meaning the records published from then on were a curated selection. “There was no online database at the time, so I scoured local libraries and old newspapers to find the records that existed to beat,” Olmsted said. The idea that clients today could have a plethora of records presented to them or created bespoke for a fee did not sit comfortably with Olmsted, even if the records themselves were kept to the same meticulous standards. Did it cheapen the achievement? “No, I’m sure the record will still be challenging.” He paused. “I don’t look down on you for having a consultant,” he finally said, “but I do look up on me.”

A few days after our call, Blakeman sent through a list of potential records for me to beat. There was an onion peeling and slicing record (too tear-jerking). There was a record for keeping three balloons in the air, which stood at over an hour (not something I wanted to practise for). Could I beat the world record of an hour and 15 minutes of downward-facing-dog? That evening I rolled out my yoga mat. After half an hour my palms started to burn, like secular stigmata. I decided to give up, but by now my feet had locked themselves in position perpendicular to my shins. My housemate had to lift me by the stomach and rest me on my side. It was ten minutes before I could move my feet.

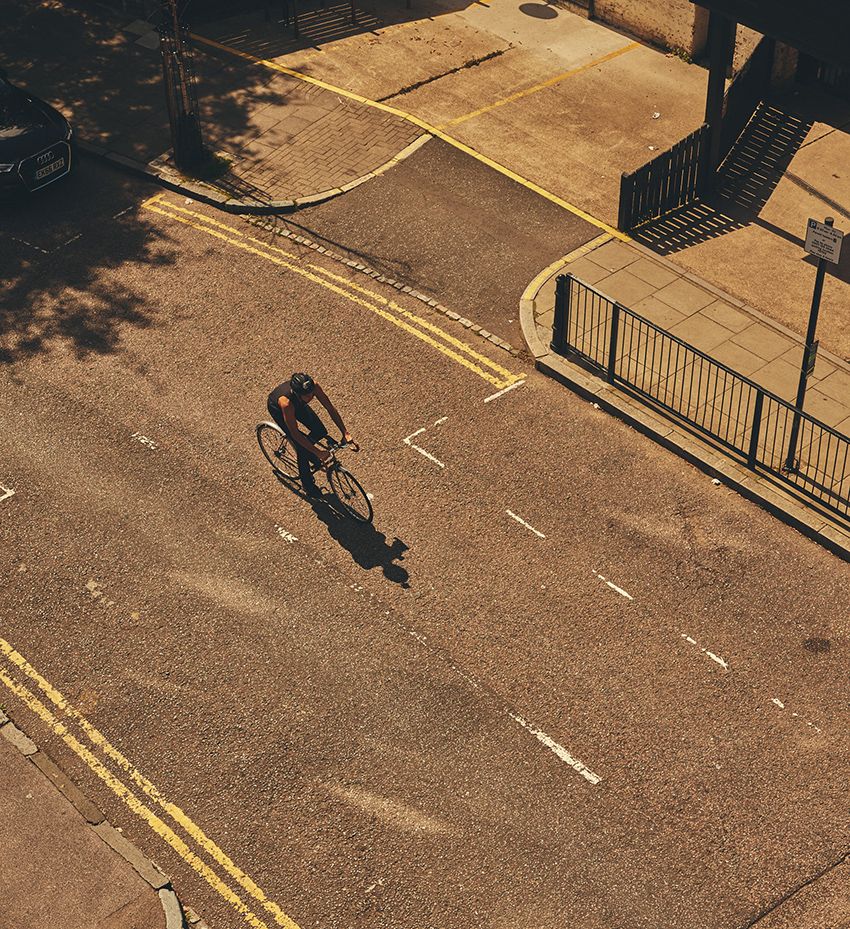

Returning to Blakeman’s list, I spotted another appealing record: the fastest time to travel to all 28 sites on the London Monopoly board by bicycle. No individual had yet tackled it. (In 2021, a team completed the ride in 2 hours and 42 minutes.) Blakeman set the target for an individual at 2 hours 30 minutes – only if I got under that time would I be considered a Guinness World Record holder.

I looked up the London Monopoly board. Many of the stops happened to be close to The Economist’s office, which is just off the Strand – itself a property on the board. Intrigued, I asked Blakeman to send me the record guidelines, which stretched to five pages. They included the definition of an acceptable bicycle (a non-electric, ordinary bike with pedals, that was commercially available), and dictated that I would need to take a time-stamped selfie at every stop, with me and the street sign or an identifiable landmark also visible. I would also need to submit continuously recorded video evidence and a GPS file showing my exact route and timings. My feat had to be recorded by two independent witnesses with stopwatches, accurate to the hundredth of a second.

Remembering what Olmsted had said about the democratic ethos of the GWR, I decided to use the same ancient single-speed bike I ride to work on (a friend who does Ironman triathlons on a carbon-fibre bicycle described mine as a pair of dustbin lids connected by scaffolding). I started out with a recce of the stops by my office one evening: along the Strand, up Bow Street, past the Royal Opera House, and through Leicester Square before turning towards Trafalgar Square.

On subsequent outings around the Monopoly board, I realised that the record was less about cycling and more about logistics. The guidelines said I could tick off the stops in any order I liked, so I got in touch with a former London cabbie. He had passed The Knowledge, a fiendishly difficult navigational test – surely he would have some tips.

The first question he asked was whether I would have to cross the Thames. Yes, I said – although the only stop south of the river is the Old Kent Road. He said that’s where I should start. He also told me to work out the farthest points east (Whitechapel Road) and west (Park Lane or Marylebone Station), and map out the quickest route between them.

The best way to finesse the route was by cycling it over and over again. Initially, I covered 40km travelling between stops. By the end, thanks to working out shortcuts and ensuring there were no wrong turns, I had got the journey down to 23km. One of the nicest things about the training was discovering new corners of the city, like Vine Street, nestled behind Regent’s Street. It is accessible via Man in the Moon Passage, the kind of street name that evokes gas lamps and fog – a Dickensian London near-buried by high rises and co-working spaces.

It wasn’t all smooth sailing. My social life took a hit – I had to duck out of dinners with friends so that I could train when the roads were emptier in the evenings. I had multiple near-collisions with vans. Passersby gave me odd looks: who was this madman riding full pelt down a street, skidding to a halt and taking a selfie in front of a road sign before cycling off again?

My exertions made me wonder why people go to such physical and mental lengths to break a record, particularly a niche one. I called Ian Robertson, a neuroscientist and author of “The Winner Effect: The Science of Success and How to Use It”. “There hasn’t been another time in which there is so much social comparison,” said Robertson. “Everyone is a brand, and it’s all about getting people’s attention.” For him it was no surprise that GWR had thrived in the social-media age: it offered validation, and hoisted people on to pedestals of their own making.

He told me about a finding in psychology, which is that “people who win the Oscars in any category go on to live, on average, three years longer than those nominated in the same category. The same is true for Nobel prizewinners, who outlive nominees by on average a year and a half.” Those people had achieved something so great they no longer needed to compare themselves to others. Pedalling along Whitechapel Road at high speed one evening, I wondered if I too would enjoy the briefest taste of immortality.

Early one Sunday morning in August, I finally made my official record attempt. I cycled out from the Old Kent Road; there was no traffic, and the weather was a perfect 20℃: warm, but not enough to make me sweat. My two timekeepers – my flatmate and one of our friends – dressed up as the Monopoly man (and woman) and sounded a klaxon for me when I set off (as stipulated in Blakeman’s guidelines).

By this point I had ridden the route enough times to know it by heart. I glided through Leicester Square, well before throngs of tourists would have made it impassable. I had to take a photo in front of a multi-storey car park, to represent the Free Parking square on the board (Blakeman allowed me some poetic licence: where in central London is there genuinely free parking?). I ticked off Vine Street, dodged a bus on Euston Road and puffed my way up the hill to Pentonville prison. The selfies became progressively more haggard. I finished outside the Angel Islington in north London – formerly a pub, now a bank. I’d managed the ride in just over an hour and 12 minutes, halving the record set by the team in 2021.

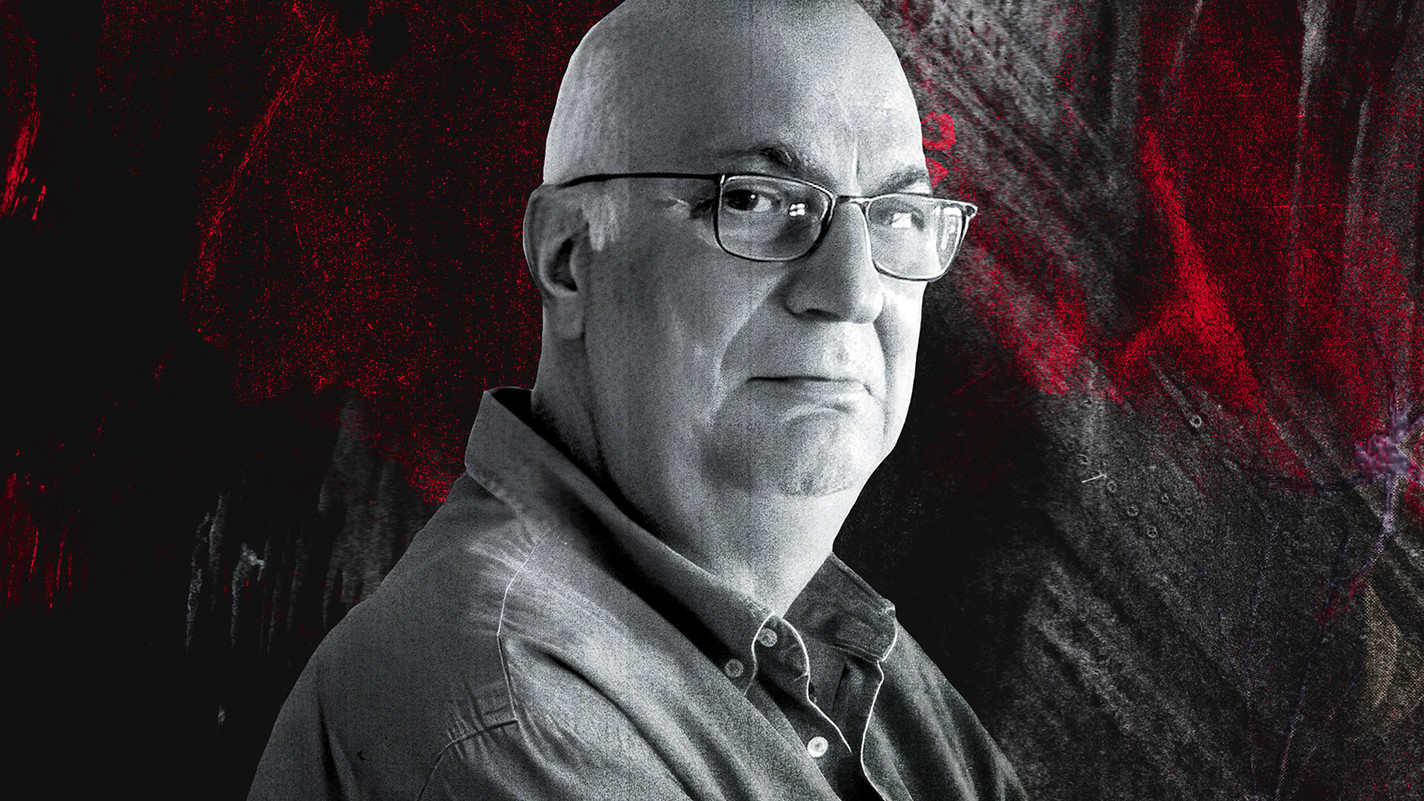

The next day I cycled with heavy legs to GWR’s office in central London. As I entered a man with a wide smile and thick-rimmed glasses crossed my path. His name was Craig Glenday, and he has been the editor-in-chief and the institutional memory of the GWR for the past two decades. He was carrying a water pistol, which he gingerly placed into a glass cabinet full of objects. Noticing my curious gaze he explained that it came from one of the world’s largest water pistol fights (in 2007, between 2,671 people in Spain) and had been kicking around his living room for a few years. He beckoned me closer to the cabinet and pointed out some of its contents. (A piece of rock, inlaid with a fossilised fish bone and spine of an ancient cuttlefish, was apparently the oldest piece of vomit ever found.) “I need to set up an iPad here with info on everything,” he said. “Otherwise, who will know what all this stuff is when I’m gone?”

I continued to chat with Glenday in the break room. He remembered his excitement at being offered a job at GWR in the 1980s: “For me, it was like some weird magical castle in the sky or something, you know, and I expected to walk into the foyer and see conjoined twins on reception and giants filing things and all that.”

It still retained some magic, I thought, staring at a portrait of Glenday by the man with the world’s longest tongue, who was able to curl his appendage round a paintbrush. (You could tell it was Glenday by the glasses.) I asked him whether GWR’s consultancy arm had changed the way he thought of the place. “People think we’re a quango or like a governmental organisation,” Glenday said, “but we’re a profit-earning business. We had to evolve to survive.” In a way he found it flattering that people thought the organisation might have sold out: “It just means that people see us as being more than just a book. We’ve become a cultural phenomenon.”

It wasn’t surprising that GWR had realised that the fervent desire of people to have their odd skills and habits recognised as special created a business opportunity. But the book exists only because of GWR’s fastidiousness, and its embrace of strange feats. “We are very pedantic,” Jack Brockbank, an adjudicator who would assess my record attempt, told me with a chuckle before he went to look at my materials. He would parse through the various items I had uploaded to the GWR records portal the night before, including the video I had taken of the route with a Go-Pro camera attached to my helmet, and all of the selfies.

Brockbank returned, 20 minutes later, carrying a mounted certificate. With a flourish, he presented me with the record, in front of Glenday and a smattering of employees who happened to be using the staff kitchen. I felt childlike and giddy, amazed that this certificate actually meant something to me. Someone in full Lycra and with a fast bike will inevitably huff and puff their way around London in pursuit of my record, and of an ephemeral moment of greatness. Good luck to them – records are made to be broken. ■

Barclay Bram produces podcast series for The Economist

PHOTOGRAPHS WILL HARTLEY

More from 1843 magazine

Thousands of Gazans are stranded in Israel and the West Bank

Many say they were rounded up by the police, beaten and dumped at checkpoints

The biblical archaeologist finding the victims Hamas burned

Bodies have been reduced to ash. Entire families are wiped out. Dismembered limbs are jumbled together

Israel’s top hostage negotiator on dealing with Hamas

In 2011 David Meidan managed to get one person out of Gaza. Now he’s trying to free 240