Lawmaking in Britain is becoming worse

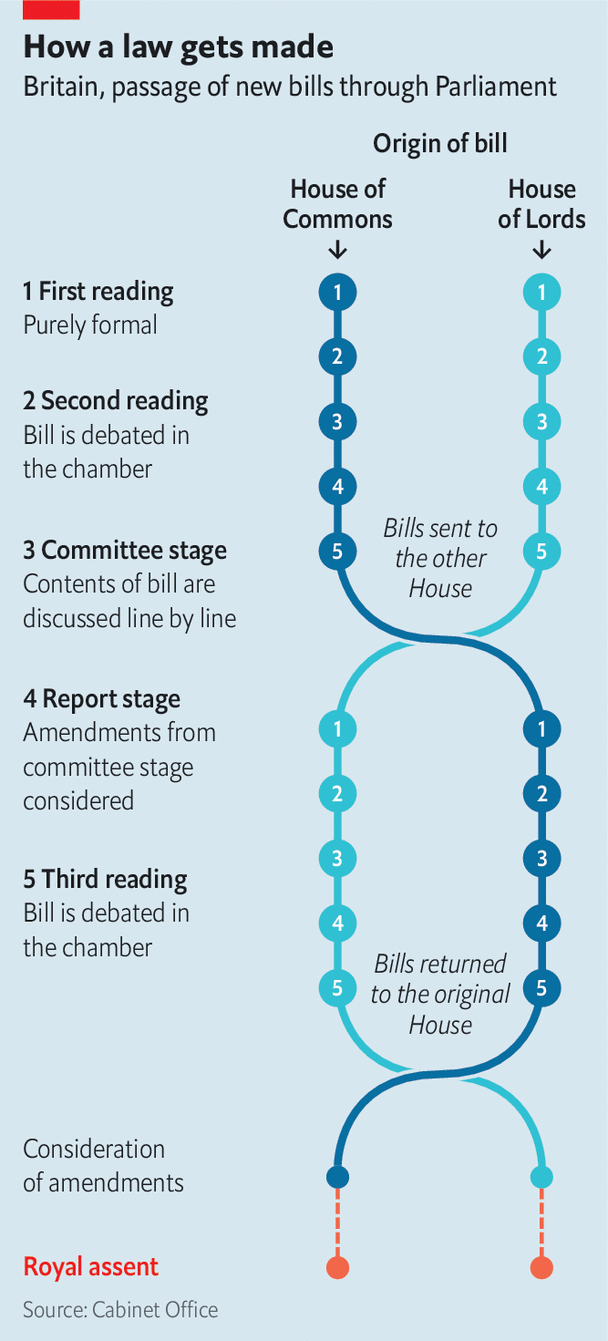

Hasty drafting, less scrutiny, more errors

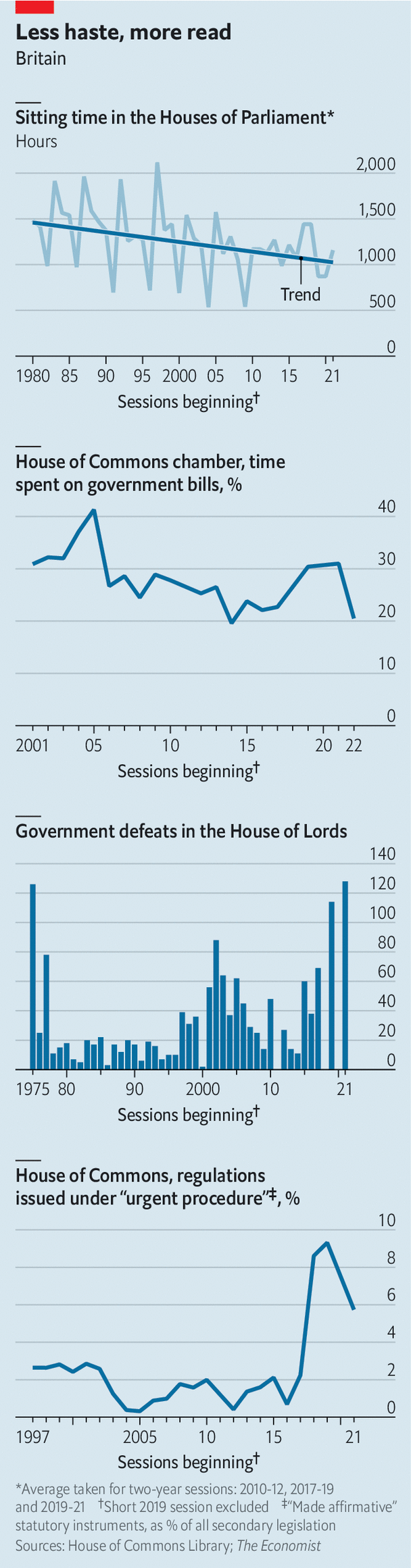

When civil servants in Britain first learn about how laws are made, they are given a board game. “Legislate?!” was devised by the Office of the Parliamentary Counsel, which drafts government legislation. The players roll dice and move counters as they steer legislation around Whitehall and through Parliament. They turn over cards revealing the hurdles of the system. “Forget to signify Queen’s Consent. Go back 2 spaces.” “New programme motion needed. Miss a turn.” The first player to have their policy become the law of the land wins.

As with many family games, much of the procedure that governs Parliament is a product of custom rather than of iron laws. The rules can be bent. Corners can be cut. And that is what is now happening. Parliament’s most vital job is to scrutinise legislation, and it is neglecting it.

This is no rubber-stamp body. The bills set out in the King’s Speech on November 7th will not sail through unopposed. Prime Minister’s Questions is as raucous as ever. Rebels still humiliate their leaders in late-night votes. But the theatre of confrontation obscures the fact that MPs spend increasingly little time on fine-bore examination of proposed legislation. Laws are too often driven through Parliament at speed. A swaggering executive at times treats scrutiny as an inconvenience. This is not just constitutionally objectionable. It also has practical costs. This is a story of how the machinery of lawmaking can start to fail, almost unnoticed.

Some of the obstacles to thoughtful legislation are structural. Governments must pack lawmaking into a tight timetable. As a result, they are habitually resistant to accepting amendments to bills. The Cabinet Office’s legislative handbook warns ministers that changes must be “kept to a minimum” since each will delay progress, note Jess Sargeant and Jack Pannell of the Institute for Government, a think-tank, in a recent report. For the same reason, the government usually balks at publishing draft bills before the parliamentary process begins. Since 1997 an average of only one in eight bills per session has undergone pre-legislative scrutiny, finds Ms Sargeant.

A second problem lies with bill committees, which are meant to hear evidence and undertake line-by-line scrutiny of bills as they make their way through Parliament. Many MPs regard them as a form of drudgery; independent-minded ones with a real interest in the proposed law are unlikely to be picked by party whips. The resulting debate is partisan and cursory. Major constitutional bills, and some others, are by convention heard in a “committee of the whole house” in the main chamber. That allows all MPs to have a say but is bad for close textual scrutiny. Across 177 bills between 2015 and 2021, 73% of them were subject to no oral-evidence hearings at all.

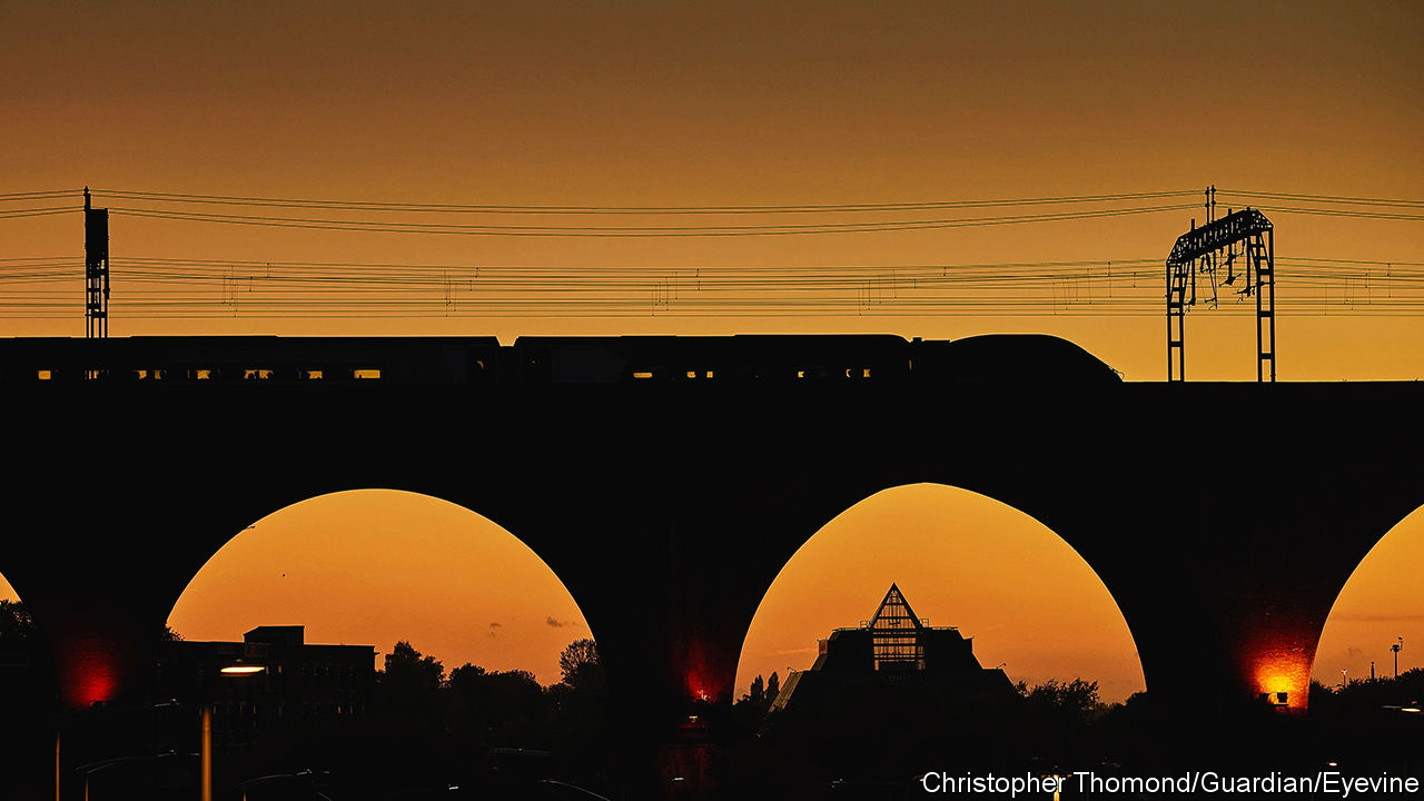

These long-standing problems have been compounded by other trends (see charts). Parliament produces more legislation than ever: the volume of acts and statutory instruments grew from 760 pages in 1911 to over 15,200 by 2009, when the data series ends (perhaps the printer jammed). Regulatory regimes for immigration and welfare have grown more complex. Brexit landed Westminster with responsibility for dense EU rule books.

Yet the House of Commons is trying to do more in less time. It was sitting for 173 days in 1988 but only 147 days in 2021. The average sitting day has shrunk from nine hours and four minutes to seven hours and 37 minutes over the same period, in part owing to sensible reforms to make the place more family-friendly.

These shorter hours are also being used differently. The share of time spent on government legislation in the chamber fell from a recent-era peak of 41% in 2005-06 to 20% in the most recent session to June. Urgent questions—a procedure whereby a minister is summoned to Parliament at once, almost always to comment on the day’s headlines—have exploded, from four in 2007-08 to 104 in 2021-22. A greater share of time is spent on Westminster Hall debates, non-legislative sessions for MPs to air their pet causes.

The fête of the nation

MPs’ jobs have come to resemble those of “super councillors”, lobbying for their constituencies, rather than legislators with their mind on the national picture. In 2017 the Hansard Society, a research outfit focused on Parliament, polled the public to ask what they thought MPs should do with their time. “Making laws” came eighth, below “representing the views of local people in the House of Commons” and “participating in local public meetings and events”. Between 2010 and 2019, the proportion of MPs representing a constituency in the region of their birth rose from 45% to 52%, including 60% of those newly elected in 2019.

Changes in the media landscape mean that ambitious MPs get less recognition for scrutinising legislation than their predecessors did. Until two decades ago, many broadsheets had a “yesterday in Parliament” page written by full-time “gallery” reporters. Now attention is focused elsewhere. “The incentive structure is misaligned,” says Ruth Fox of the Hansard Society, who reckons that MPs don’t get any credit or benefit in the constituency for being a good scrutineer of legislation.

Politicians also lack expert support. MPs’ staffing budgets are intended to fund four full-time assistants, with pay for the most senior capped at £56,312 ($69,000). Many are young; turnover is high. In America’s Congress, a representative can employ up to 18 full-time staff, often including legislative specialists. Members of the House of Lords have no paid personal researchers at all.

This weakening system of scrutiny has been hit by two great shocks. Brexit meant that the government needed to race against time to rewrite the statute book to get ready for separation from the EU. Covid-19 forced lawmakers to move even faster.

Few dispute that speed was necessary. But the Brexit referendum introduced a shrill and aggressive politics that treated parliamentary scrutiny not as a service to voters, but as a betrayal of them. And there is growing concern, certainly among senior members of the House of Lords, that ways of legislating in times of crisis have become a new modus operandi. Civil servants, too, say that covid and Brexit have altered ministers’ expectations about the time needed to properly draft a bill. A generation of MPs elected since 2015 knows little different.

“For three years at least ministers seem to have regarded legislation as a series of party political broadcasts,” says Lord Lisvane, formerly the most senior clerk in the House of Commons. A committee of cabinet ministers, chaired by the Leader of the Commons, is tasked with vetting draft laws before they enter the system. “But it seems a very soft touch these days. Ministers simply aren’t put in the dock about their legislative aspirations,” he says.

In recent years a growing number of bills have completed their main Commons stages (the second and third readings) in a single day, almost eliminating the chance for meaningful scrutiny. Some instances of haste were justifiable: to pass covid legislation or to change the royal household after the death of the queen.

Others were less excusable. The Energy Prices Act, dashed out by Liz Truss’s government in 2022, underpinned a £78bn programme of universal household and business subsidies. Analysts and MPs had proposed much cheaper targeted designs, but the Tory leadership contest that summer crowded out proper policy work. The act implementing Boris Johnson’s Brexit trade agreement cleared the Commons and Lords in a single day on December 30th 2020; in contrast, ratification of the Maastricht treaty of 1992 was considered over a period of more than 400 days.

As a result of this haste, the details of laws are being worked out later in the process. In particular, ministers are asking for ever-broader powers today that will let them make policy tomorrow. Secondary legislation is law created by ministers through regulations known as “statutory instruments”, and made under powers given to them by an act of Parliament. Conventionally, primary legislation is used to set policy (such as a new criminal offence) and secondary legislation to guide its implementation (such as setting the level of fines). But the boundaries are not precisely defined. The growing use of secondary legislation prompted the House of Lords in 2021 to warn that “government by diktat” was leaching power from Parliament.

“Skeleton bills”, which provide ministers with the framework powers to make a policy, but few clues as to what it will be in practice, were essential in the Brexit years as ministers prepared to take on old EU powers in areas such as fishing and chemicals. But their usage has become part of a pattern. The Strikes (Minimum Service Levels) Act, a law intended to keep trains and schools running during industrial disputes, was “almost so skeletal that we wonder if bits of the bones were stolen away by wild animals and buried somewhere”, declared Sir Jacob Rees-Mogg, a Tory MP.

Skeleton bills often depend on “Henry VIII” powers, named for the Tudor king’s habit of governing by proclamation. These are clauses which state that ministers can amend past, or even future, acts of Parliament by issuing secondary legislation. Lord Judge, a former head of the judiciary, declared in a recent speech that they have become so common that “when an act of Parliament omits a Henry VIII clause it is only because someone in the department has failed to press the relevant button on the computer.”

Lord Blencathra, a former Tory minister, complains that since Brexit departmental lawyers have been “tacking them on to tiddly little bills” on the basis of “just in case”. A bill now before Parliament, intended to prevent public bodies from engaging in boycotts of Britain’s allies, contains five Henry VIII clauses. The Online Safety Act contains more than 20. Individually, these clauses may be justifiable; collectively, they point to a government seeking shortcuts in the legislative process.

Statutory instruments get even less scrutiny than primary legislation. They are presented to Parliament and sifted by committees of lawmakers, but debates on them can last just minutes or seconds. They cannot be amended, but only voted down, which is rare. The last time the House of Commons blocked a statutory instrument was in 1979; the House of Lords last did so in 2015. The legal commitment to hit net zero by 2050, made in 2019, is likely to be the most expensive policy decision Britain will take this century. It was set by a statutory instrument after a 90-minute debate in the Commons and without a vote there, using a mechanism created in the Climate Change Act of 2008.

Under a procedure called “made affirmative”, some statutory instruments become law as soon as a minister signs them; lawmakers vote on them later. The Economist’s review of parliamentary data shows that this technique has been used far more liberally recently—from 1.8% of the statutory instruments in 1997-2019 to 8.1% in 2019-22. Covid is mostly to blame.

All this haste is leading to less informed decisions. MPs often pass legislation with no idea as to its costs or benefits. Many impact assessments, which are meant to quantify the expected effects of proposed statutory instruments, “appear to have been scrambled together at the last minute to justify a decision already taken”, concluded a recent House of Lords report. The Home Office’s impact assessment on the Illegal Migration Bill revealed that deporting a person to Rwanda would cost £169,000 and would only be cost-effective if many thousands of people were deterred. But it was not published until June 26th, two months after it had cleared the Commons.

Errors are also rising. Some 11% of the statutory instruments laid in the 2022-23 session of Parliament were to correct previous drafting mistakes, more than double the 5% threshold that the House of Lords Secondary Legislation Scrutiny Committee considers acceptable for human error. “The real problem is that this is such a convenient way of doing things,” says Lord Thomas, a former Lord Chief Justice who sits on the committee. “And when you do something because it’s convenient, that is what really ought to cause you to worry.”

Good scrutiny has historically depended on the interplay between the House of Commons, which takes the lead on setting policy, and the unelected House of Lords, which has focused on revising and fine-tuning legislation. Many members of the upper house feel that they are doing the basic scrutiny that the Commons is shirking, and that the government pays their work less heed. Traditionally, the Lords has cajoled the government into making its own amendments to flawed bills. That process has broken down, leading the Lords to vote against the government more often. It has inflicted 370 defeats since December 2019, compared with 268 in 2010-19.

“When you see a larger number of defeats, a significant amount of it is down to greater government intransigence rather than greater Lords aggressiveness,” says Professor Meg Russell of University College London. Sometimes they succeed in forcing a reversal. More often the amendments are thrown out when a bill returns to the Commons and have no impact.

Strikingly few Conservative MPs are animated by how the rules of the parliamentary board game are being forgotten. But should an election force them into opposition, the costs of a weakened Parliament will be more obvious to them. Labour Party officials insist they will restore discipline to the process. But a Labour government would inherit a statute book packed with powers that could prove rather useful to ministers in a hurry.

Take the Retained EU Law (Revocation and Reform) Act, passed earlier this year, which creates wide-ranging powers for ministers to rewrite regulations that predated Brexit. Its neo-Thatcherite architects hoped it would ignite a deregulatory Big Bang. But it might as easily be used to strengthen trade-union rights or realign policies with those of the EU. “These powers could sit there for decades, being used by governments who may take an entirely different approach,” says Dr Fox. “That does not seem to compute at all with ministers.” The rules of the legislative game exist for the benefit of all the players. When they are bent, everyone ends up losing. ■

For more expert analysis of the biggest stories in Britain, sign up to Blighty, our weekly subscriber-only newsletter.

This article appeared in the Britain section of the print edition under the headline "Bad laws"

From the November 11th 2023 edition

Discover stories from this section and more in the list of contents

Explore the editionMore from Britain

Suella Braverman uses a pro-Palestinian march to sow discord

The right to protest is fundamental—as is an independent police force