Does America have enough weapons to support its allies?

It could face wars in the Middle East, Ukraine and Taiwan

To read more of The Economist’s data journalism visit our Graphic detail page.

WHEN AMERICA provided Ukraine with weapons to resist Russia’s invasion in 2022, many people asked whether it would also have the means to deter a Chinese assault on Taiwan. That question is all the more relevant now that Israel, another ally, is at war with Hamas. President Joe Biden has insisted that America will help its allies defend themselves, acting once again as the world’s “arsenal of democracy”, as President Franklin Roosevelt promised the country would be in 1940. Does Mr Biden have the weapons he needs to keep his word?

In general America sends different weapons to Israel, Taiwan and Ukraine, but when demands overlap they put pressure on the availability of some weapons (see table). Take air-defence missiles. All three allies have stocks of the Patriot, an expensive but effective missile system, for use against incoming missiles and aircraft. They also have the Stinger, a shoulder-fired missile capable of taking down low-flying aircraft. (The Avenger is a vehicle-mounted version of the Stinger.) All these battle-proven weapons are, however, in limited supply. In a recent assessment Mark Cancian of the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), an American think-tank, deemed the Patriot to be “available but with some limits”, while stocks of Stingers and Avengers were “extremely limited”, because demand for them is high and spare parts are hard to find.

Javelins are also in short supply. These anti-tank missiles feature a fearsome combination of power and precision. Javelins in Ukraine, together with other anti-tank missiles, have taken out huge numbers of Russian tanks. Taiwan’s arsenal of these American portable weapons systems may be helping to deter China. And although Israel has less need for anti-tank weapons, because Hamas does not have a serious fleet of armour, they could prove useful in urban warfare, for instance against fortified strongpoints, given their precision targeting, according to Mr Cancian. But getting hold of them will not be easy. An analysis by The Economist last year found that America may have given away more than a third of its stock of these weapons. CSIS now puts that share at 40%, making their supply extremely limited in a three-war scenario.

Stocks of other weapons not included in the CSIS tally are also depleted. For instance, 155mm artillery shells are in short supply; America has reportedly diverted to Israel a consignment intended for Ukraine. And war games suggest that, in a conflict over Taiwan, America would quickly run out of the long-range anti-ship missiles that would be most useful in repelling an invasion.

Many defence experts think that the shortages are a sign of America’s inadequate investment in munitions in recent years. The reality of two wars—and the possibility of a third—is beginning to change that. America is increasing investment in the production of mortars, artillery, ammunition, rocket-propulsion systems and the microelectronics that increasingly go into modern munitions. These investments may give America’s adversaries pause for thought.

America also has adequate stockpiles of many other weapons popular among its allies. Mr Cancian reckons that only a dozen of the 100 types of weapons sent to Ukraine since 2022 are in short supply. And the war between Israel and Hamas, for now, appears to be largely contained within Gaza, which should ease pressures on additional military aid. Still, should the world descend further into chaos, America would be at risk of becoming an overstretched superpower.■

More from Graphic detail

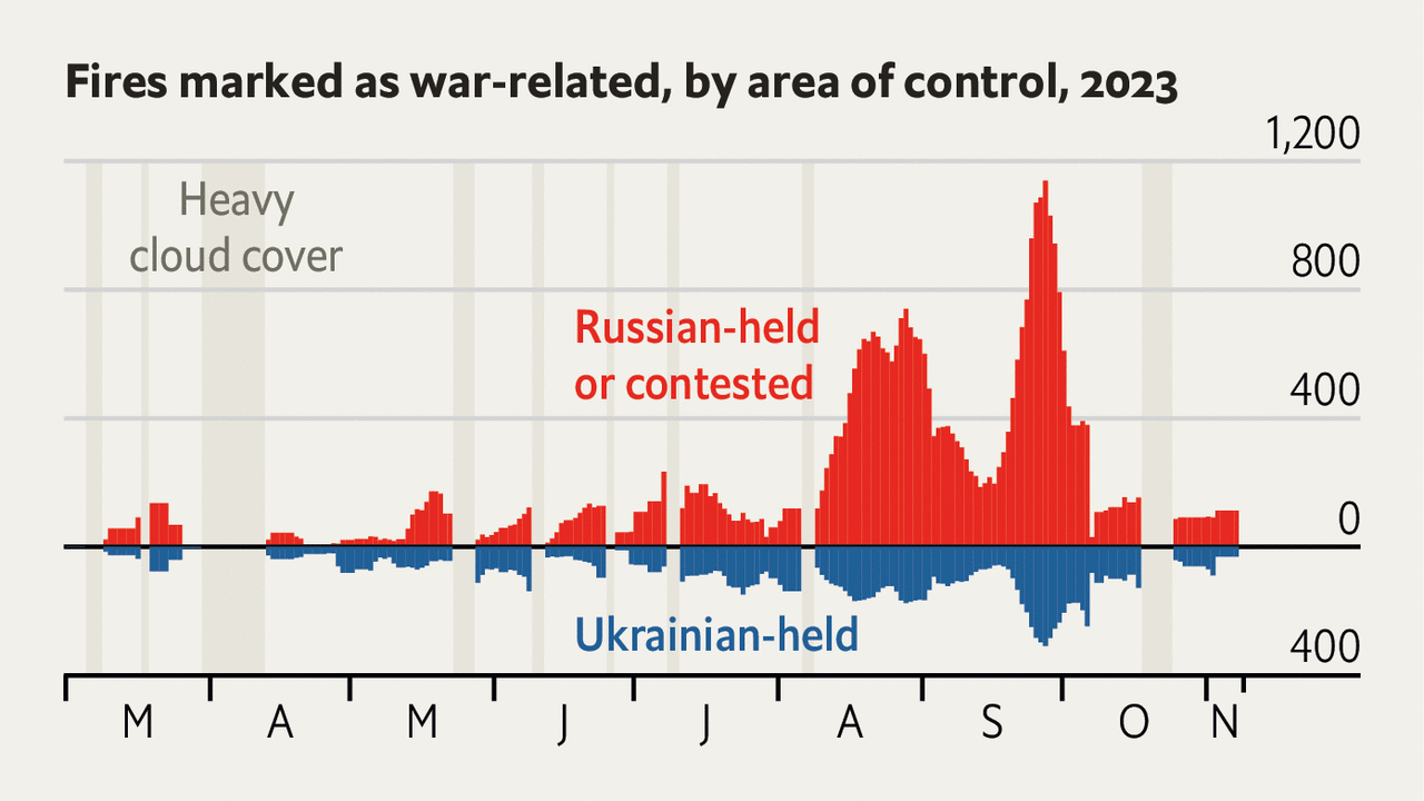

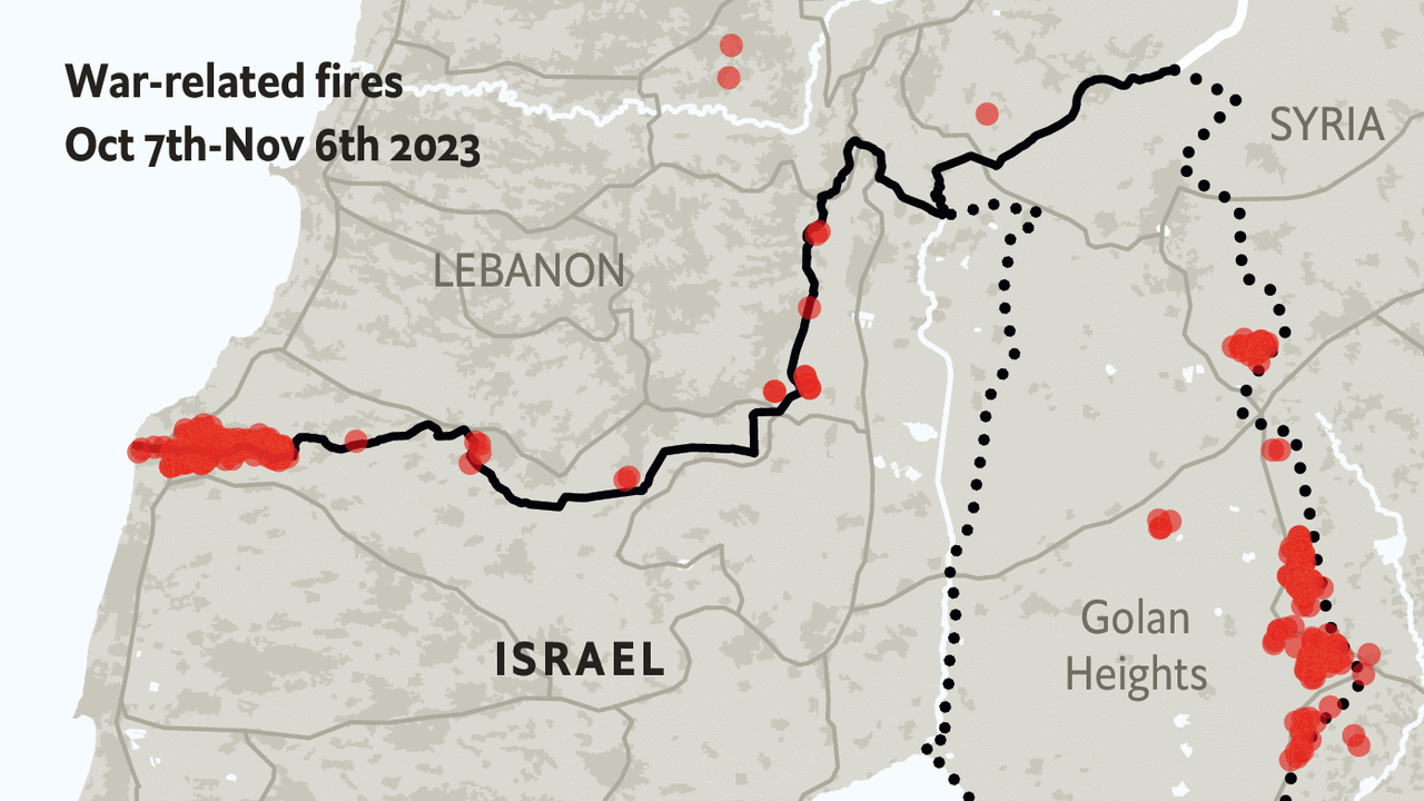

The threat of Hizbullah can be seen from space

Our satellite data can map the risk of a widening conflict

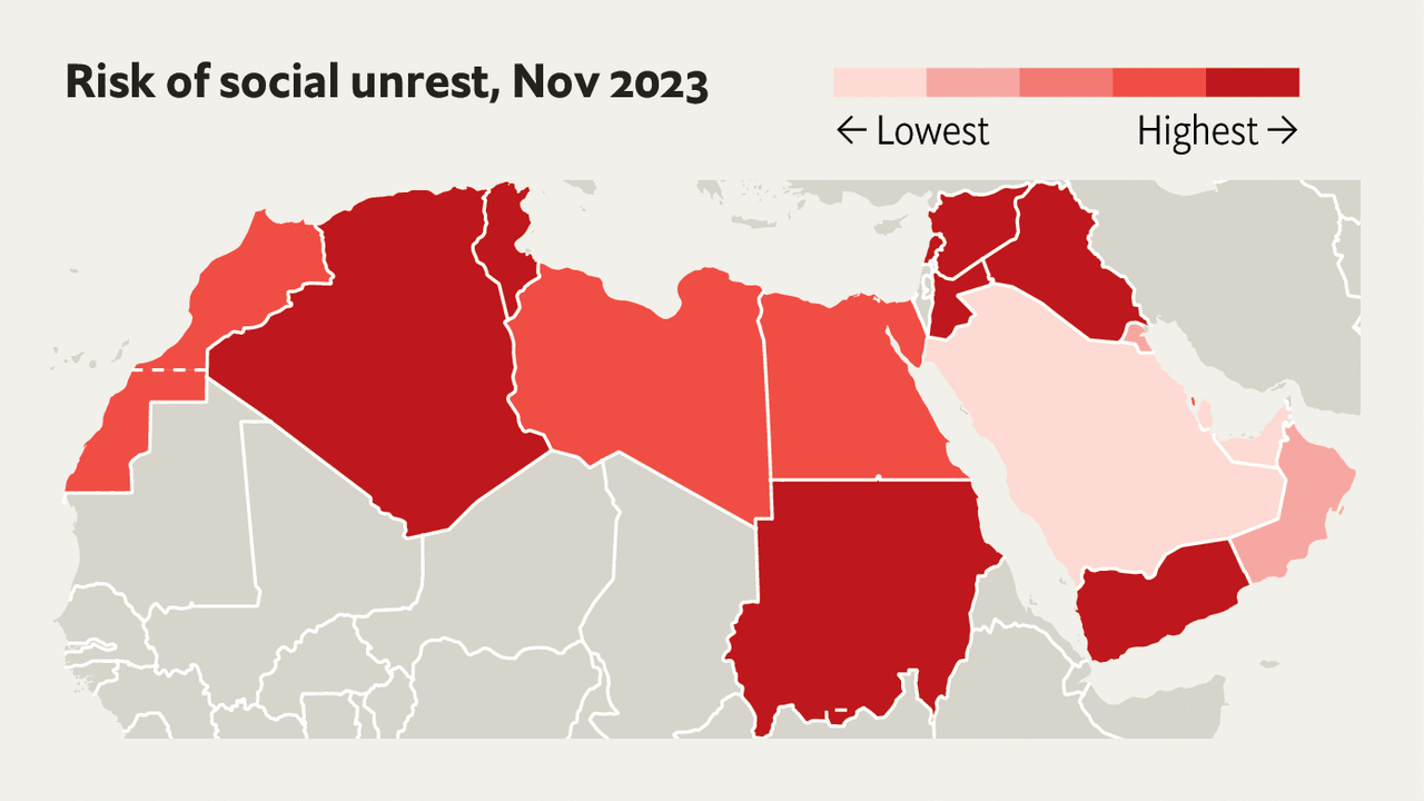

Could the Israel-Hamas war trigger unrest across the Arab world?

Three countries are now more vulnerable to instability, according to EIU’s risk modelling